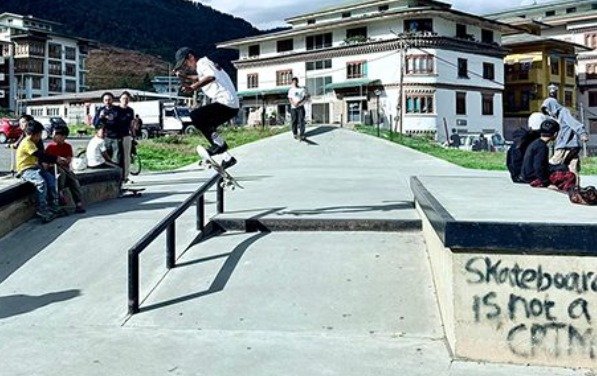

At 19, Singye Rinchen’s life has already taken more falls and recoveries than most people see in a lifetime. Each scar on his hand tells a story, not of defeat, but of determination that keeps him rolling forward on the concrete slopes of the Johnny Strange Skatepark in Babena, Thimphu.

“I broke my hands twice,” he says, lifting his wrist that no longer straightens fully. “But I didn’t stop skating. Even when I had the plaster on, I went back to the park.”

Singye’s skateboarding journey began during the COVID-19 lockdown. With no internet access and plenty of boredom, he borrowed a skateboard from a friend, a girl whose board happened to stay with him during the lockdown and began learning tricks in his neighborhood.

“At first, it was just to pass time. My father wouldn’t give me the internet, so I started skating every day. That’s how it started,” he recalls with a grin.

When restrictions eased, he made his way to the Johnny Strange Skatepark, a place he had often passed by on walks home from school in Zilukha to Jungshina.

That spark grew into a full-blown passion. In 2021, Singye officially began skating, guided by senior skaters like Mipham and Pema, the coordinator of the Bhutan Skateboarding Club.

“They taught me how to jump and balance. Slowly, I started learning the tricks and understanding the culture of skating,” he shares.

But his journey was not easy. His parents, especially his mother, were not supportive. “My mother always told me to focus on studies. She doesn’t believe in sports as a career. Even when I broke my hand, I lied to them and said I fell on the stairs. But they knew it was from skating,” he said.

Despite the tension at home, he found support in the skate community. “Acho Pema and the club helped me with shoes and boards when mine wore out. They trust me now because I never stopped skating. They have hopes for me that I’ll do better and improve the culture in Bhutan,” he says.

He said, “Now, I don’t have to ask my parents for shoes or skateboard parts. I can manage myself.”

Though the number of skaters in Thimphu has declined from a dozen regulars to just a handful, Singye remains optimistic. “At one time, there were around 10 or 12 of us skating regularly. Now it’s me, a younger brother, and a few kids. But I think there will be more opportunities in the future,” he says.

His hope mirrors the vision of Bhutan’s skateboarding community, small but resilient, with growing international recognition. Global groups like “Salad Day Skate” who brings international professionals every year to Bhutan in collaboration with Bhutan Olympics Committee shows the increasing recognition and interest.

At the Johnny Strange Skatepark, as the afternoon light catches the chipped surface of his board, Singye pushes off once again proof that some dreams can keep rolling, no matter how many times you fall.